Genesis 10 and 11: Babel and the Table of Nations

BAY-bul, not BABB-ul

The 10th chapter of Genesis begins with a genealogy called "The Generations of Noah," and goes on about it for 32 verses. Chapter 11 ends with a 23 chapter expansion on part of that genealogy, called "The Generations of Shem." Together these are called the "Table of Nations."

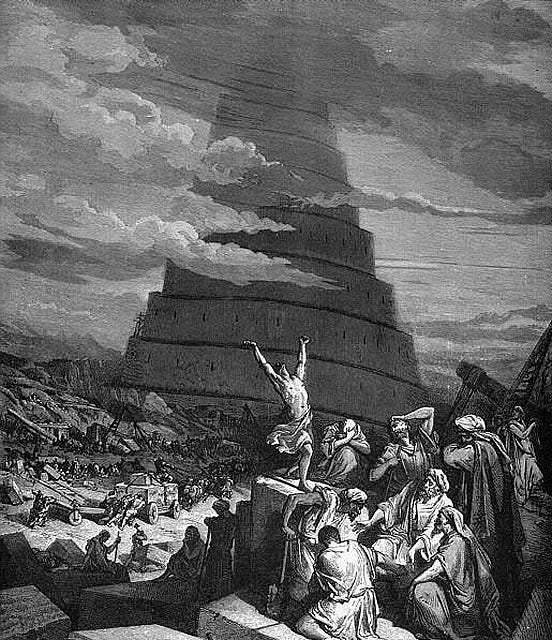

But stuck smack dab in the middle is a nine-verse story--the last of the so-called "mythological matter" of Genesis--familiar to all as "The Tower of Babel."

In my summary here, I have chosen to rip that story out of its context and present Genesis 11:1-9 first, followed by the Table of Nations. Because why not? Besides, some conservative scholars suggest that the Tower of Babel story occurs chronologically at the start of Chapter 10.

The story of the Tower has all the historicity and factuality we've come to expect from a book full of talking snakes and universal floods. The genealogy, on the other hand, bridges the story of the mythical (or at least legendary) Noah with the slightly-more-historically defensible story of Abram-who-became-Abraham, looked to by both the Jews and the Muslims as the Father of their People.

The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1563) (Wikipedia)

The Story I: The Tower of Babel

All humans were mutually intelligible--that is, they spoke the same language. And when they arrived on a plain called Shinar (Mesopotamia), they decided to build a city and a tower out of brick; this was meant, it seems, to establish their reputation and give them some sort of social cohesion, "lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth."

The god comes down for a look-see, and says, "These people are working together and speaking one language. We can't have that, because who knows what achievements it might lead to?"

So he decides to go down and "confound their language," the most famous element of the story, and then "scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth." Harsh.

The Story II: The Table of Nations

Before and after the Babel story (why was it stuck in the middle?) is a mess of genealogy. Let me offer a summary that offers a semblance of order, but is no less confusing than the original.

A "T and O map" from 1472 shows the three known continents (Asia, Europe and Africa) marked "Sem" (Shem), "Iafeth" (Japheth) and "Cham" (Ham). East is at the top. (Wikipedia)

Noah, as we know, had three sons: Shem, Ham, and Japheth.

A. Japheth had seven sons: Gomer, Magog, Madai, Javan, Tubal, Meshech, and Tiras.

Gomer, the eldest, had three sons: Ashkenaz, Riphath, Togarmah.

Javan, the third, had four sons: Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim.

And all of these "divided the isles of the Gentiles"--remember, Japheth is traditionally believed to be the progenitor of the Europeans.

B. Ham had four sons: Cush, Mizraim, Phut, and Canaan. (Remember, these are places associated with Africa and the western parts of the Middle East.)

Cush had six sons: Seba, Havilah, Sabtah, Raamah, Sabtecha, and--notably--Nimrod, a "mighty hunter before the LORD."

Cush's son Raamah had two sons (I think): Sheba and Dedan.

Nimrod by David Scott, 1832 (Wikipedia)

Verses 10:8-12 interrupt the genealogy, first to talk about Nimrod, and then to give a list of cities founded by Ham's (or Cush's) sons: Babel, Erech, Accad, Calneh, Asshur, Nineveh, Rehoboth, Calah, and Resen.

Then the list of the descendants of Ham picks up again.

Ham's son Mizraim had (at least) seven sons: Ludim, Anamim, Lehabim, Naphtuhim, Pathrusim, Casluhim (out of whom came Philistim,), and Caphtorim.

Ham's son Canaan had some sons--Sidon his firstborn, and Heth--but also founded a number of nations: the Jebusite, the Amorite, the Girgasite, the Hivite, the Arkite, the Sinite, the Arvadite, the Zemarite, and the Hamathite. (We're told here that later the families of the Canaanites spread abroad.)

Here, the territory of the Canaanites is described (including such well-known places as Gaza, Sodom, and Gomorrah).

C. Finally, Shem had five sons, including "all the children of Eber": Elam, Asshur, Arphaxad, Lud, and Aram.

Aram had four sons: Uz, Hul, Gether, and Mash.

Arphaxad had a son, Salah, who himself had a son, Eber.

Eber had two sons (Shem's great-great-grandsons): Peleg and Joktan.

Joktan had thirteen sons(!): Almodad, Sheleph, Hazar-maveth, Jerah, Hadoram, Uzal, Diklah, Obal, Abimael, Sheba, Ophir, Havilah, and Jobab. Their territory is then briefly described.

We now skip over the story of Babel (11:1-9) and continue the genealogy in verse 10, repeating and expanding on the descendants of Shem, including the ages at which they "begat" and died. You can see all that in the text below. Note should also be taken that there were other sons (as we can assume throughout the genealogies), as well as daughters. Shem gets special treatment--a closer focus--as progenitor of the Jewish people who wrote and assembled the Hebrew scriptures.

D. Naming only the direct line, Shem's descendants are:

Arphaxad, Salah, Eber, Peleg, Reu, Serug, Nahor, and Terah.

So Terah is Shem's 6x-great-grandson. And he had three sons (named): Abram, Nahor named for his granddad?), and Haran.

Haran was the father of Lot, whose wife will become famous, as we shall see in Chapter 19.

Abram married Sarai; and Nahor married Milcah. Milcah's father was Haran (so she was Nahor's first cousin?) and her sister was Iscah. Sarai (famously) had no children--yet.

Terah and his brood had been living in Ur of the Chaldees, and he moved the whole lot to Canaan (minus Haran, who had died in Ur). Confusingly, the place they moved to in Canaan was also called Haran (maybe they named it, in honor of Terah's dead son?).

Phew! I thought we'd never finish this.

But most important to us are Abram and Sarai, who will star in the next 15 chapters, give or take, and remain important even into the New Testament.

Universal Event, or Homely Folktale?

It is not my intention to put you to sleep. There will be some Footnotes on the genealogy, but most of what I really want to say in this lesson is in regard to that danged tower.

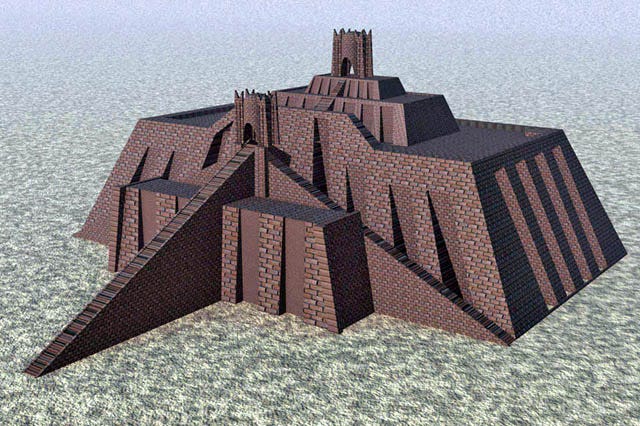

Imagine this: A bunch of desert nomads are camping out near the remains of a ziggurat, one of those "stepped" or terraced pyramids (though actually dating to before the Egyptian pyramids) found in the ancient Mesopotamian cultural sphere. We know they were part of temple complexes, the precursors of which dated back to the sixth millennium BCE.

In fact, the Greek historian Herodotus reported that ziggurats had shrines on their top platforms (none of which platforms survive today). Some conservative scholars, like Rev. Halley, suggest that their entire purpose was "idolatrous worship, and herein lay the sin of the Babel builders."

But you couldn't expect the nomads to know this. So when a child asks, "Grandpa, what's that big pile of bricks over there?" Grandpa busts out with this story. "Ya see, kid, the people decided to challenge the god by building a stairway to heaven..."

Except this isn't what the story says at all. Ask anyone who knows their Bible, though, and that's probably what they'll tell you. But look again. The people's motives were this: to become famous ("make a name for ourselves") and to remain together ("otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.")

As I phrased it above, "to establish their reputation and give them some sort of social cohesion." And what's wrong with that? Nothing about "becoming like the god" or "challenging his authority" or anything like that.

Now, some True Believers think that merely by settling down together ("they dwelt there"), the people were defying the god's order to "multiply upon the earth" (see Genesis 8:17). By confusing the languages, he was just kicking them out of the nest, as it were.

Okay, maybe that part about the top reaching unto heaven is a cause of concern (see next); but (a) why take it literally? and (b) do you think the god was really dumb enough to worry that somehow the people were going to storm the pearly gates? I'd like to think that ancient people considered him to be smarter than that.

Maybe, though, this "heavens" thing is an echo of the fact that the tops of the ziggurats were probably used as astronomical observatories. An early aspect of civilization (the making of cities) was "reading the sky" to determine the best timing for everything from planting (and avoiding seasonal floods and droughts) to making war. (This is the very reason--I kid you not--that we call the third month of our year "March." It was the time when the weather was conducive to going forth to war.)

At any rate, imagine a typical dad saying, "Hey, you kids, I want you to get along with each other. Here, why don't you build a sand castle? Oh, but wait, first I'm going to make it so you can't communicate with each other, and then I'm going to scatter you up and down the beach. Try to cooperate now!"

It makes no sense. But returning to the campfire: Grandpa tells a cool story about why the ziggurat is unfinished (mistaking its ruined condition for incompletion), while simultaneously explaining why there are different languages in the world, and the whole thing sort of hangs together.

And then we come along and take the folktale for gospel, and somehow try to draw from it a lesson about the nature of the god (What? That he's a spoilsport? That he doesn't want us to get along? That he's insecure about his position at the top of the heap?) instead of just appreciating it as a good yarn.

The Dark Tower

But there is a darker interpretation that, with a willing suspension of disbelief (or a dogged insistence on a certain kind of belief) one could overlay on the story.

The "top in the heavens" line is seen as evidence of hubris, or a kind of over-arching ambition--which ties in nicely with the idea of gaining praise for their prowess in building such a marvel. And the god is having none of that. "Pride goes before destruction" and all that.

You see, humans are not meant to succeed aside from the god's help (some believe), and to do so is to insult the god. As I mentioned in Lesson 3, the serpent's seeming ability to live forever (based on the shedding of skin) without the god's help was thought to be somehow "against the plan," as it were. Self-sufficiency is suspect. (Some have made the same argument for condemning the joy of sex--one should have no ecstatic experience outside of prayer.)

Likewise, any wished-for unity achieved without the god's help is a merely human and therefore unacceptable goal. The people must be indivisible only "under God," ya know.

And so, rather than seeing this story as proof that the god is an insecure bully who goes around kicking the sand castles of kids who haven't included him in their play, we are to believe that the drive toward architectural excellence and social community--the engines of progress--are somehow evil impulses that must be nipped in the bud. They must be "restrained" from any other marvels they might "have imagined to do."

(Now I must add: the Biblical account does not show him kicking the tower down; it is simply abandoned. But other traditional sources portray the god as being more proactively destructive.)

The Tower of... What? Where?

Incidentally, one of the most famous ziggurats still in existence is at Ur, arguably the place where Terah and Abram/Abraham's family came from. Also, the timing works out:

the ziggurat at Ur was completed in the 21st century BCE, shortly before the "patriarchal age" is somewhat presumptuously presumed to have taken place;

and it was in tatters and was restored by Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, in the 6th century, around the time when the texts we're reading were probably produced.

Reconstruction of the Ziggurat of Ur, based on the 1939 reconstruction by Sir Leonard Woolley (Wikipedia)

My hypothetical story-teller could have lived closer to the latter date than the former; major theories have been promulgated on flimsier evidence!

But really, I'm just blue-skying. Several candidates for "the" Tower have been proposed and argued over. But I think any standing ruins would have served as the focus of such a yarn.

The Walls of Babylon and the Temple of Bel (Or Babel), by 19th-century illustrator William Simpson (Wikipedia)

A look at the Hebrew shows that the tower was Babylonian (Babel-onian--get it?). But the name babel is glossed in the Genesis story as meaning "confused," the writer(s) himself/themselves "confusing" it with the Hebrew verb balal. But 260 times the King James Version translates the same root (babel) as "Babylon" or "Babylonian," and only twice as "Babel"--both times in Genesis 10 and 11.

So let's call it the Tower of Babylon, shall we?

Incidentally, the word's similarity to the English word "babble" is sheer coincidence. It derives from onomatopoetic words in the Germanic ancestors of English that imitate "the repeated syllable ba, typical of a child's early speech" (from "Google’s English dictionary... provided by Oxford Languages").

Toponyms and Ethnonyms and Eponyms--Oh My!

Why is the story wedged in here, after the genealogy and before the expanded genealogy? Conservative scholars suggest a simple (if not downright simplistic) answer: it happened, they opine, in the midst of all this, and it accounts for the creation of the many nations named here. E unus pluribum. (Actually it should be Ex Uno Plures, but my point might be lost in the correct translation.)

For make no mistake: What we have here is a list, not so much of individuals, as of cities and kingdoms. Remember, at this stage of civilization, cities often were kingdoms, and vice versa.

In fact, as mentioned, a high-falutin' name for the lists in Genesis 10 is "The Table of Nations." So if you had taken Geography 101 back in the day (the millennia-BCE day) these are the places you would have had to memorize for the test. In technical terms, these names are toponyms (names of places) and ethnonyms (names of ethnic groups), purporting to be eponyms (names of people after whom places and ethnic groups have been named).

The Confusion of Tongues, a woodcut by Gustave Doré (Wikipedia)

So the "confusion of tongues" has been inserted into a rather dry portrayal of the "confusion of nations" resulting from the spread of humanity across the earth.

An Anti-Pentecost?

True Believers assert that the "Gift of Tongues" at Pentecost (see Book of Acts Chapter 2) was some kind of legit reversal of Babel: suddenly, through the help of the Holy Spirit, people were speaking "in other languages," and foreigners nearby were "bewildered, because each one heard them speaking in the native language of each."

Icon depicting the Theotokos (the Virgin Mary) together with the apostles filled with the Holy Spirit at the original Pentecost (Wikipedia)

I don't really see this as the anti-Babel. After all, they weren't using language to clarify or communicate--it was bewildering! Furthermore, most of the "speaking in tongues" I've ever witnessed was not manifested in people suddenly being able to speak in Sanskrit or Swahili, but in people making nonsensical noises--dare I say… babble?

--------

Text and Footnotes, coming right up!

The Generations of Noah (The Table of Nations) (10:1-32)

The Text: The Sons of Japheth (10:1-5)

Note: I will try to limit my Footnotes to a few individuals or places in this welter of names. You can consult this Wikipedia article section if you're dying for more details.

10:1 Now these are the generations of the sons of Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth: and sons were born to them after the flood.

10:2 The sons of Japheth are Gomer, Magog, Madai, Javan, Tubal, Meshech, and Tiras.

10:3 And the sons of Gomer are Ashkenaz, Riphath, and Togarmah.

10:4 And the sons of Javan are Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim.

10:5 The isles of the Gentiles were divided up by them; every one according to his language, family, and nation.

10:1 Noah, Shem, Ham, and Japheth: These were discussed last time.

10:2 [whole verse]: Dr. Scofield (on what authority I know not) gives peoples associated with every name in this verse: Gomer: the Celtic family; Magog: the Scythians (Tartars); Madai: the ancient Medes; Javan: those who peopled Greece, Syria, etc.; Tubal: the inhabitants of the region south of the Black Sea, and Spain; Meshech (with Magog and Tubal): Russia; Tiras: the Thracians.

10:5 isles: The Hebrew word 'iy can also be translated "regions," making this the region of the Gentiles, i.e. Europe, long associated with Japheth.

10:5 every one according to his language: Here, as at verses 20 and 31, it's indicated that there were many languages. Yet in 11:6 we're told, "the people... have all one language." But placing the Tower story chronologically first solves this problem.

The Text: The Line of Ham (10:6-14)

10:6 And the sons of Ham are Cush, and Mizraim, and Phut, and Canaan.

10:7 And the sons of Cush are Seba, Havilah, Sabtah, Raamah, and Sabtecha; and the sons of Raamah are Sheba and Dedan.

10:8 And Cush fathered Nimrod, who became a mighty one on the earth.

10:9 He was a mighty hunter before the LORD, so it became a proverb: "Even as Nimrod the mighty hunter before the LORD."

10:10 And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, Erech, Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.

10:11 Out of that land Asshur went forth and built Nineveh, and the cities of Rehoboth and Calah,

10:12 And Resen between Nineveh and Calah; that's a great city.

10:13 And Mizraim fathered Ludim, Anamim, Lehabim, Naphtuhim,

10:14 Pathrusim, Casluhim, (out of whom came Philistim,) and Caphtorim.

10:6 And the sons of Ham... Cush is identified by some with Ethiopia; Mizraim is an old name for Egypt; Phut may also be Ethiopia; and Canaan covers the area of modern Israel, the "Promised Land."

10:8 Nimrod: That Nimrod was "mighty," e.g. a king, has given rise to a legend that it was he who commissioned the Tower of Babel, helping to explain why the story of that Tower has been unceremoniously plopped into an otherwise perfectly boring narrative. And sponsorship of the Tower would explain why he gets a fuller profile here than any others do.

10:9 a mighty hunter: This can be taken literally in a time when a leader had to protect his people from wild beasts; or it could be symbolic of his prowess as a warrior.

10:10 And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel: So Babel was "Nimrod's kingdom," which was located in Shinar, an old name for Mesopotamia. Thus the royal association mentioned in the Footnote to 10:8.

10:10 Erech: The "Uruk" of the Epic of Gilgamesh (one of my favorite books)

10:11 Asshur: as in "Assyria"

The Text: The Canaanites (10:15-20)

10:15 And Canaan fathered Sidon his firstborn, and Heth,

10:16 And the Jebusite, the Amorite, the Girgasite,

10:17 The Hivite, the Arkite, the Sinite,

10:18 The Arvadite, the Zemarite, and the Hamathite: and afterward the families of the Canaanites were spread abroad.

10:19 The border of the Canaanites was from Sidon--as you come to Gerar--to Gaza; as you go to Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, and Zeboim, even to Lasha.

10:20 These are the sons of Ham, according to their languages, families, countries, and nations.

The Text: The Line of Shem (10:21-32)

10:21 Children were born to Shem also, the father of all the children of Eber, Japheth's brother.

10:22 The children of Shem are Elam, Asshur, Arphaxad, Lud, and Aram.

10:23 And the children of Aram are Uz, Hul, Gether, and Mash.

10:24 Arphaxad fathered Salah; and Salah fathered Eber.

10:25 Eber had two sons: one was named Peleg ["divided"], for in his days was the earth divided; and his brother's name was Joktan.

10:26 And Joktan fathered Almodad, Sheleph, Hazar-maveth, Jerah,

10:27 Hadoram, Uzal, Diklah,

10:28 Obal, Abimael, Sheba,

10:29 Ophir, Havilah, and Jobab: all these were the sons of Joktan.

10:30 And their dwelling was from Mesha, as you go to Sephar, a mountain in the east.

10:31 These are the sons of Shem, after their families, after their tongues, in their lands, after their nations.

10:32 These are the families of the sons of Noah, according to their generations, listed by nation: and the nations were divided by these on the earth after the flood.

10:24 Eber: Father of the Hebrews. An old tradition says Eber refused to assist in the building of the Tower, and thus the god did not confuse his language. Thus Hebrew is the original language in which the god spoke to Adam. And so on.

The Text: The Tower of Babel (11:1-9)

Note: See the many mini-sermons above regarding this passage

11:1 And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech.

11:2 And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there.

11:3 And they said one to another, Let's make bricks, and burn them thoroughly." And they had brick for stone, and slime they had for morter.

11:4 And they said, "Let's build a city and a tower, whose top may reach to heaven; and let's make a name for ourselves, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth."

11:5 And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men built.

11:6 And the LORD said, "Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and they begin to do this. Now nothing which they have imagined to do will be restrained from them.

11:7 "Let us go down, and confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech."

11:8 So the LORD scattered them abroad from there on the face of all the earth: and they stopped building the city.

11:9 Therefore it is called by the name Babel; because the LORD there confounded the language of all the earth: and from there the LORD scattered them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

11:2 they journeyed from the east: This suggests that people came from east of Mesopotamia, but the traditional landing site(s) of Noah's ark would have been to the west or north.

11:3 slime had they for morter: I don't know what tickles me more, that tar is called "slime," or that the KJV misspells "mortar."

11:6 "the people is one, and they have all one language": See Footnote at 10:5 above.

11:7 Let us go down: There's that plural god again; see Lesson 1.

11:9 Babel: As mentioned above, this is "Babylon"; but the early editors (ironically) confused it for the Hebrew word balal, which means "confuse."

Zooming in on the Generations of Shem (the "Semites") (11:10-32)

The Text: The Generations of Shem (11:10-26)

11:10 These are the generations of Shem: Shem was a hundred years old, and fathered Arphaxad two years after the flood:

11:11 And Shem lived five hundred years after he fathered Arphaxad, and fathered sons and daughters.

11:12 And Arphaxad lived thirty-five years, and fathered Salah:

11:13 And Arphaxad lived four hundred and three years after he fathered Salah, and fathered sons and daughters.

11:14 And Salah lived thirty years, and fathered Eber:

11:15 And Salah lived four hundred and three years after he fathered Eber, and fathered sons and daughters.

11:16 And Eber lived thirty-four years, and fathered Peleg:

11:17 And Eber lived four hundred and thirty years after he fathered Peleg, and fathered sons and daughters.

11:18 And Peleg lived thirty years, and fathered Reu:

11:19 And Peleg lived two hundred and nine years after he fathered Reu, and fathered sons and daughters.

11:20 And Reu lived thirty-two years, and fathered Serug:

11:21 And Reu lived two hundred and seven years after he fathered Serug, and fathered sons and daughters.

11:22 And Serug lived thirty years, and fathered Nahor:

11:23 And Serug lived two hundred years after he fathered Nahor, and fathered sons and daughters.

11:24 And Nahor lived twenty-nine years, and fathered Terah:

11:25 And Nahor lived a hundred and nineteen years after he fathered Terah, and fathered sons and daughters.

11:26 And Terah lived seventy years, and fathered Abram, Nahor, and Haran.

11:11 fathered sons and daughters: Note again, throughout, that there are other offspring besides those mentioned, including daughters.

11:24 Terah: There's a tree of Terah's descendants here.

11:26 Abram: Halley suggests that there were 427 years between the flood and Abram/Abraham.

The Text: The Generations of Terah (11:27-32)

11:27 Now these are the generations of Terah: Terah fathered Abram, Nahor, and Haran; and Haran fathered Lot.

11:28 And Haran died before his father Terah in the land of his birth, in Ur of the Chaldees.

11:29 And Abram and Nahor took wives. The name of Abram's wife was Sarai; and the name of Nahor's wife was Milcah, the daughter of Haran, who was the father of both Milcah and Iscah.

11:30 But Sarai was barren; she had no child.

11:31 And Terah took Abram his son, and Lot the son of Haran his son's son, and Sarai his daughter in law, his son Abram's wife; and they went forth with them from Ur of the Chaldees, to go into the land of Canaan; and they came unto Haran, and dwelt there.

11:32 And the days of Terah were two hundred and five years: and Terah died in Haran.

11:28 [whole verse]: I can't figure out why it's important that "Haran died before his father... in Ur of the Chaldees." Perhaps we'll find out later.

11:30 But Sarai was barren: This tidbit, mentioned in passing, will become of great importance soon.

--------

And that dang near ties a bow on things. In the next lesson we'll dive into the story of Father Abraham.

'Til soon!