"A Humanist Looks at the Bible"

Subscribe to the Weekly Lesson. It's free!

Howdydoo, I'm James Baquet, and I'd like to tell you a little bit about this project and how it came about.

The plan is to write an explanatory lesson on one passage from the Bible, to be published every weekend (in time for Sunday morning reading, wherever you are). The list I'm working from has around 230 sections; I may add some to this, or combine some together, but in the end I expect there to be about 250 "lessons," starting with the first chapter of Genesis and ending (gulp!) with Revelation--not line by line, mind you, but covering the whole story nonetheless.

Incidentally, I'll be using the King James Bible, slightly-modernized by yours truly. It is in many ways the most reliable English version, but the thees, thous, thys, and thines , as well as the hasts, wasts, werts, and goeths, need a little updating. As we go along, I'll refer to other versions, too, for clarity.

--------

"How dare I?" you may well ask. Read on.

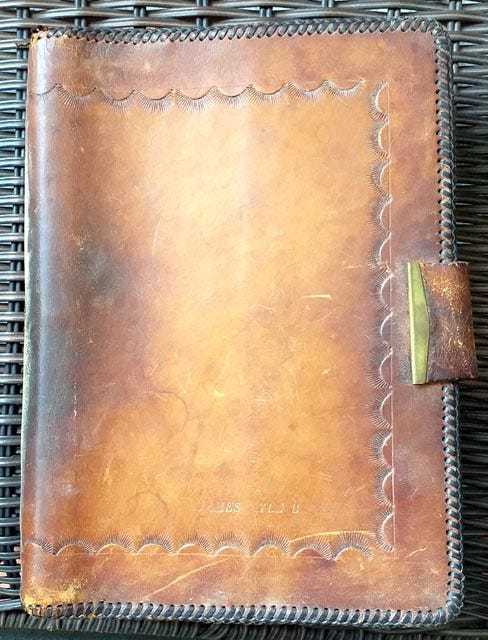

My loose-leaf Scofield Reference Bible in the cover my leather-working aunt made for it. The stain on the left is from my hand from carrying it for years.

Me 'n' the Bible

I grew up in the Episcopal Church, which in those days wasn't too well known for its emphasis on Bible study. True, we had the Book of Common Prayer, which some like to think of as "the Bible rearranged for worship." And yeah, we had Bible lessons in the Sunday service. But "Bible totin'"? Nope.

After confirmation by a priest I highly admired (whose son and confirmation-class-mate was my best friend then, and still a good friend), for several years I toted my prayer book and aspired to the priesthood.

Me in the band with my Scofield (in its original, store-bought cover). You can see how the stain got there!

But then, in my late teens, I jumped onto the tail-end of the "Jesus movement"--sort of sanctified hippies--and lived in a house of "brethren," became a Bible-study leader, and even played trombone in a "Christian rock 'n' roll band."

I was insufferable.

The best thing about that black-and-white time was the grounding I got in the Bible, under the influence of excellent (if fundamentalist) teachers and my own avid studies of the classical commentators: Spurgeon, Matthew Henry, Lightfoot, Halley, and above all, C. I. Scofield, whose Scofield Reference Bible I carried and read--well--religiously. And repeatedly. I'll be using it and some of those other sources in this project.

Time went on, and I returned to the Episcopal Church, working on the staff of three parishes, in one case for four years as principal and lay chaplain of a day school. (Nothing clarifies one's understanding of a topic like having to express it to primary schoolers!) Meanwhile, I did two part-time years--equivalent to the first of three full-time years--in an Episcopal seminary.

And then, I got disillusioned. Since then, I've wandered through "the world's religions" and ended up seeing things more or less as a Buddhist.

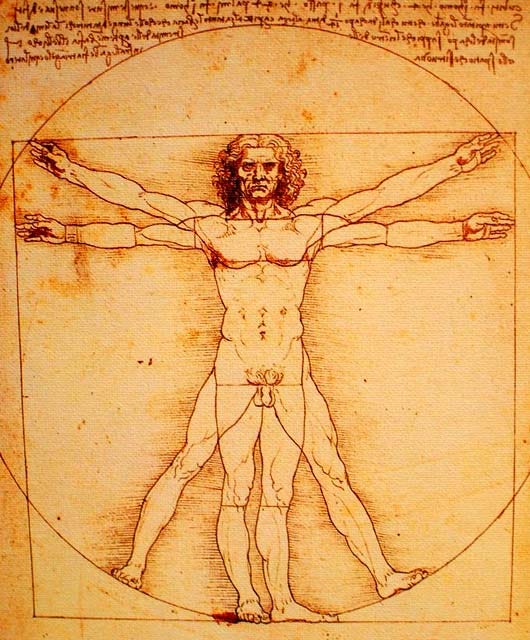

da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (Wikipedia)

Me 'n' Humanism

What, exactly, is Humanism?

Well, you probably know the words "Atheism" and "Agnosticism." These, by virtue of the "A-" at the beginning, tell you what someone doesn't believe in. "Humanism" tells you what someone does believe in.

In short, I believe in us.

Despite plenty of evidence to the contrary, I believe that we as human beings have the capacity to solve any problems we have created (like poverty, hunger, war, and so on), and to lessen the impact of those we haven't (like earthquakes, tsunamis, and devastating fires).

We are also capable of great art, architecture, literature, music, and the other achievements of culture.

And the opposite--unnecessary death, famine, destruction, oppression, etc.--when wrongheadedness prevails.

The Bible has been a powerful resource for two millennia; the very counting of those millennia springs from its events. And many of the greatest works of art, music, and literature in many of the world's cultures are interpretations of its stories and themes. So, believer or not, we are all influenced by it one way or another, and it behooves us to understand it a little better.

But I'll try not to preach.

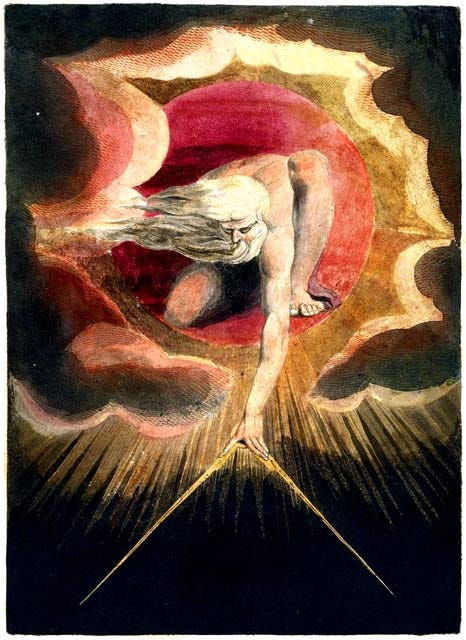

William Blake's Ancient of Days (Wikipedia)

The God Question

The Jews have a saying: "Where there are two people, there are three opinions." Or something like that. Heck, self-identified Christians can't even agree on the importance of the Bible! To some, it is the whole and inerrant Word of God, containing everything we need to know about--well, everything. For others, it is subservient to tradition and the Church's leadership. And to still others, it's a book of "fairy tales." More on that in a minute.

Incidentally, an official (though not the official) position on the Bible in the Episcopal Church evoked the image of a three-legged stool: the sources of Anglican authority are scripture, tradition, and reason in balance. Shorten one leg, the stool tips; remove one and it falls over.

How much harder, then, is it to agree on the "right" concept of "God"? Who or what is God? A unity? A trinity? Transcendent? Immanent? Merciful? Vengeful? Immutable? In process? Incomprehensible? Known? Loving? Jealous? Infinite? Limited?

For the sake of this project--and to ensure that the broadest number of people will find value in it--I will be treating God--perhaps somewhat controversially--as a character in a story. Or several stories, by different authors. In the late 70s, when I was in thrall to evangelicalism, I took a class in the local community college called "The Bible as Literature." The teacher did a masterful job of redirecting class discussions away from personal beliefs (including mine) to the consideration of the Bible texts as stories. That, for the most part, is what I hope to do here, with occasional nods toward one "theology" or another.

A "Joke" (?)

As for the readers of this project, let me try to establish a few categories.

First, a "joke":

A man walks into a doctor's office with a frog on his head. The doctor looks at him and asks, "What happened?" and the frog says, "Well, it started as a wart."

Let's divide the audience of the joke into four kinds of listeners. The first type in our audience is a hardheaded realist, who insists that every element of a joke be literally true before it can be funny. "Aw, heck," he says, "frogs can't talk. That joke is disqualified from being funny." Another, more broad-minded, person says, "I recognize that the frog's ability to talk is intrinsic to the story, but I will suspend my judgment on the possibility of frogs talking in order to appreciate the story at face value. After all, the value of a joke lies in its ability to make me laugh, not its historical authenticity." Another member of the audience has absolute faith in the joke teller, and believes everything he says: "If the teller of this joke says frogs can talk, then by golly frogs can talk!" And a fourth, more "spiritually-minded" listener, may say, "There is a crucial lesson in this joke, and the frog's ability to talk is indicative of some deeper meaning, far removed from mere questions of biology. I will try to go beneath the surface of the joke to try to discern the real meaning of the frog's ability to speak."

Let's call these four "The Rationalist," "The Liberal," "The True Believer," and "The Mystic." The Rationalist insists that all elements of a joke--or a text--accord with his scientific/materialistic world view before he can accept it; The Liberal will take all jokes and work with them on the same practical, human level, regardless of any "supernatural" elements in them; The True Believer slides right past the issue on skis of Faith; and The Mystic tries to see through the difficult point to access its deeper significance.

Despite the differences in approach, these four listeners have one thing in common: they all approach the joke in hopes of getting something out of it: a laugh, a chuckle, a smile, or, perhaps in this case, a grimace. They are all, in some sense, seeking satisfaction from the joke; they are all potentially members of a "Faith-in-the-joke" community.

The Rationalist, however, because of his standards of Faith, has rejected the joke outright. It can have no value for him, because it does not meet his a priori criteria for validity. Some might say he is judging the joke, not on standards based on its purpose, but on standards alien to the very spirit of the joke.

The Liberal, on the other hand, has made acceptance or rejection of the joke a non-issue, concentrating on the "human value" of the joke. He seeks in the joke nothing more than it purports to offer. It is a vehicle of humor, not history.

The True Believer has accepted the joke dogmatically, insisting that it bears not only humor, but history as well. The precariousness of this position is evident: If one could break through his dogged acceptance and prove to him that the joke "never happened," it would shake his ability to benefit from the joke to its very foundations.

Finally, like The True Believer, The Mystic has put his faith in the joke, albeit at a different level: The Mystic sees the joke as something to be seen through, as a signpost toward a deeper experience of life.

My approach to the Bible, as you might have guessed, will be closest to that of the Liberal.

Little Red Riding Hood (Wikipedia)

History? Science? Fairy Tale? Myth?

I also want to put to rest, as we go along, certain "straw men" set up by militant atheists. One of them is that "the Bible is a book of fairy tales."

It is not.

It certainly has some elements that feel like fairy tales: talking animals (snakes, donkeys); "magic" (water into wine, figures suddenly appearing and then disappearing again; raising the dead); a surface lack of moral complexity (God is entirely good, the devil entirely bad); and so on.

But the difference is at either end, what philosophers call its etiology and teleology. The Bible, like any proper fairy tale, arose from a community. However, it was taken as the focus of that community, rather than merely an evening's entertainment (with a moral). And its end was nothing less than the salvation of a people. No fairy tale ever aspired to that.

Furthermore, look at the effect of that book on the world today. No one builds edifices to praise Little Red Riding Hood; starts universities in the name of Thumbelina; or goes to war over differing understandings of "The Monkey and the Crocodile."

Rather, I would say, the Bible is chock-full of myth, in the fullest and most empowered (and empowering) sense of that word: what Joseph Campbell called "an energy-evoking and energy-directing sign" or system of signs, and nothing short of the "Masks of God." Wikipedia calls them "stories that play a fundamental role in a society."

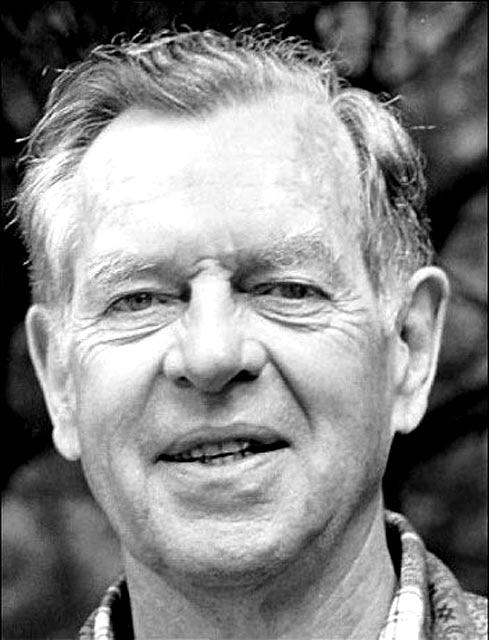

Joseph Campbell (Wikipedia)

Campbell enumerated those "fundamental roles" as:

The Mystical Function, which opens the individual to the wonder of life and the universe, characterized by awe;

The Cosmological Function, which helps the individual determine his or her place in the universe;

The Social Function, which helps to organize the lives of those living in a community; and

The Pedagogical Function, which teaches the individual how to live a human life.

These four functions overlap, of course, but they provide a useful framework in examining the myths embodied in the Bible.

Oh, one more thing about a myth? It is not necessarily untrue.

And let's not forget, the Bible also contains history, poetry, letters, instruction, pithy sayings, and sometimes just danged good stories.

Where Did the Bible Come From?

It's important to realize that the Bible is not a book, but a collection of books. In most cases, each was a separate composition (or an editing together of compositions), though some of, for example, the "history" books (like I & II Samuel, I & II Kings, I & II Chronicles, e.g.) were originally one book.

As for the selection of books to be included: Catholics and Protestants disagree on which books belong in the so-called "Old Testament." The Catholics accept a slightly broader selection, which the Protestants reduced a hair when they removed books not included in the Hebrew Scriptures. (As for those Hebrew Scriptures: the order of books is considerably different from that found in Christian Bibles.)

Furthermore, when we say someone can quote the Bible "chapter and verse"? Well, not originally. The earliest manuscripts did not divide the stories the way we do today, though there were some divisions (like paragraphs) in some texts for ease of reading. The system of chapters and verses we see today dates only to the 13th century.

Why is this important? I think we should realize that the fixed, static Bible we pick up and quote today is the end product of a long, drawn-out process of human decision-making, from the formation of the texts themselves to the finalization of a "canon" or selection of texts to be included. The True Believer says (implicitly or tacitly) that God handed it down in its current form, for all the world like Moses’s Tablets of the Law.

Most of the first portion, the so-called "Old Testament,” was written in Hebrew, though some passages are in Aramaic, a language derived from Hebrew. And the New Testament is primarily in a vernacular form of Greek, called Koine. I have studied Hebrew (Biblical and modern), as well as Koine Greek, and retain enough of what I learned to do a little word study here and there. Nevertheless, what I mainly want to deal with are the English texts as we see them today.

I'll say a few more words about this in Lesson 001, about the "beginning" of Genesis.

--------

That's enough--for now. I may well come back and add to or revise this as we go along; after all, this project may be taking place over the next five years or so!

I look forward to sharing all of this with you, and hearing your thoughtful responses.

Adios, Amigos!

And don't forget to subscribe!